|

From all the Elizabethan injunctions issued to regulate the composition and use of music in the Reformed English church, a phrase that particularly resonates is That the same may be as plainly understanded as if it were read without singing. That’s a pretty radical requirement. Just what did that mean to the listener then? What might it imply for how we should perform Gibbons’ verse anthems now? Many Reformists clearly didn’t have any time for music in worship and viewed it as a distraction, viz Erasmus (The choristers themselves do not understand what they are singing, yet according to priests and monks it constitutes the whole of religion. ......In college or monastery it is still the same: music nothing but music….), Thomas Becon, Chaplain to Cranmer (There have been … which have not spared to spend much riches in nourishing many idle singing men to bleat in their chapels, thinking so to do God on high sacrifice … music is not so excellent a thing, that a Christian ought earnestly to rejoice in it …) and many other leading figures in the reformed English church (all well documented in Peter le Huray’s superb study ‘Music in the Reformation in England 1549-1660’). Yet it is against this background that the verse anthem form emerges in the last decades of the 16thC and rapidly becomes hugely successful. In a Chapel Royal wordbook of 1635 (that is the register of texts of pieces in repertoire) there are recorded 65 ‘full’ (i.e. fully texted) anthems as against 152 ‘single’ (i.e. verse) anthems. What was it about this new musical form (there is nothing really like it in pre-Reformation music) that, so to speak, ticked the Reformist boxes? One answer must surely be that the verse anthem is supremely functional, designed not as a background to prayerful contemplation but as a highly focussed means of transmitting its text and its message. And its whole style of delivery, drawing partly on the dramatic tradition of the Elizabethan stage consort song, would surely have been very different from that which was cultivated for the old choral polyphony. Obviously, the requirements that the text should from now on be in English, not Latin, and that the setting should be syllabic, rather than melismatic (decreed in further injunctions) were designed to make it readily understood. But it goes much further than that. In the phrase as if it were read without singing the word read refers not to the listener but to the performer *, and implies a command of rhetorical declamation, the art of which was thoroughly taught in the reformed grammar schools. What we are dealing with must be a style of ‘speaking in song’ that is probably much closer to the ‘recitar cantando’ advocated by contemporary Italian theorists than the traditional Anglican way of presenting this music has led us to expect. As Caccini advises in his ‘Nuove Musiche', … la musica altro non essere che la favella e’l rithmo, & il suono per ultimo, e non per lo contrario. We are convinced that the all-purpose, blended choral style which has to fit Palestrina motets, Stainer anthems and romantic psalm-settings into the same choral evensong as a piece such as Gibbons’ highly dramatised ‘See, see, the Word is incarnate’ simply misses the point. As for whether we achieve something more successful in our recording, that will be for others to judge, but we’re certainly aiming for something very different.

* for a very interesting discussion of the implications of ‘reading aloud’ in this period, go to this presentation from @Richard Wistreich’s recent AHRC project ‘Voices and Books 1500-1800’ The anthems in our main source Mus21 involve consort instruments, yet they are not specified. Viols are an obvious choice for many of them, as were clearly used in versions of verse anthems that are found in domestic sets of partbooks, presumably for domestic worship. But we are aiming to present a variety of ways in which these pieces might have been heard, so we have cornetts and sackbuts in a couple of anthems with a more 'processional' character, such as 'Great King of Gods’, as well as one or two surprises (!). So much is still uncertain about how consort anthems may have sounded, despite argument over the often repeated orthodoxy "viols did not play in church", which continues to stifle interesting discussion (anyone remember that Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band song from the 60s "Can blue men sing the whites”?).

Until now, very little seems to have been tried with early brass in sacred English music, a recent recording of Byrd by Musica Contexta directed by Simon Ravens being a notable exception (perhaps also some performances by Paul McCreesh’s Gabrieli Consort?). There are records of professional wind players being employed at the Chapel Royal, possibly in verse anthems, and there is even record in a wordbook of the Chapel of an anthem by William Lawes with 'verses for cornetts and sackbuts’, alas with no music surviving. As for the likely pitch of such instruments, there is very little surviving physical evidence. There is apparently a tenor cornett in Norwich at a pitch of about A465 with a Bassano/Venetian maker’s mark (would any early brass players like to comment on this?) and Jamie Savan, a member of our collaborating ensemble His Majestys Sagbutts and Cornetts, has written an article to be published in the Historic Brass Society Journal (I understand early next year) which assesses surviving cornetts in Verona, Vienna and Christ Church, Oxford, all related by the Bassano/Venetian maker’s mark, and comes to some important conclusions about their pitch and how they were used. He has kindly let me see a proof, and without divulging the fascinatingly complex detail of his argument, I think I can say that it broadly supports our use of cornetts and sackbutts at A465 ‘church’ pitch for our project. At any rate, it will be wonderful to hear Gibbons’ anthems done this way, possibly for the first time since the 17th century. As for the viols, what issues does this pitch pose? For several years, since the publication of Andrew Johnstone’s article ‘As it was in the beginning’ (see previous post) Fretwork has been persuading choirs who want to perform Gibbons’ anthems to abandon their horrid minor third transpositions (who ever seriously thought that consort instruments in the early 17th century played in Bflat minor?) and compromise with transposition of one tone. That is OK as far as it goes, since the resulting keys are not impractical for viols, but it is clearly not where we ideally want to be and not what we think would have been done. So, for this project, we taking a step that we believe has never before been taken with a consort of classical (i.e. early 17th century design) English viols and tuning it at A465. To do it properly, that means selecting instruments of the right dimensions and completely restringing them for this higher pitch. Many viol players are now used to the idea that instruments of the earlier period may have sounded at A440 or even 465, but there is still a strong default attraction to 415 for everything from about 1600 onwards, especially ‘consort music’. A415 is obviously convenient, but it has for a long time seemed to me that the wide spread in sizes of surviving English viols of the period suggests the use of significantly different pitch standards. Some years ago, at a meeting of the UK Viola da Gamba society, Ian Harwood proposed that there existed two ‘families’ of English viol size exactly a fourth apart, and that this sufficiently explained the difference in surviving sizes. I took part in a demonstration in which various antique instruments and copies were used to make up two consorts, one ‘high’ and the other ‘low’. The bass of the ‘high’ choir’ was a magnificently preserved instrument by Henry Jaye (? circa 1620) commonly referred to as the ‘large Jaye tenor’ (formerly belonging to the Hill family and now in private hands) and the same instrument also formed the tenor of the ‘low’ consort, whose bass was another Jaye model, a copy made for me by Jane Julier of the 80cm string length Jaye belonging to Christophe Coin. The demonstration didn’t convince me and the proposition that an exact fourth explained the variety of sizes seemed much too neat. Much more likely, I thought then, was that the instruments which seemed to be members of a smaller family were intended to play at some kind of higher pitch standard: perhaps a ‘church’ pitch, perhaps therefore originally belonging to somewhere like a choral institution (where we know viols were used for choirboy training) or private chapel. The consort that we are assembling includes two antiques, one a small Jaye treble, which we often borrowed in the early days of Fretwork but always played at a pitch which seemed improbably low for its size. The owner is very excited at the prospect of now hearing it in this high tuning and so are we. Our Gibbons Project presents us with an opportunity to experiment with some radically new sonorities, both vocal and instrumental. We are using a performing pitch of A465 (a semitone above 440) for the sacred anthems and a major reason for choosing this is the consistency of the vocal ranges. Some decades ago in the 20th century scholars such as David Wulstan remarked upon this factor but they proposed that the pitch should be considerably higher, a minor 3rd higher than 440. However, this was largely based upon an interpretation of 17th century written evidence (referring to the so-called 'Tomkins organ pipe') which has now been shown to be mistaken. Andrew Johnstone, in his article 'As it was in the beginning' (Early Music, November 2003) demonstrates clearly how the still prevalent practice of transposing the whole 'Tudor' sacred repertoire up a minor 3rd came about through a combination of misunderstandings over how the Tudor organ developed and simple convenience for the voice ranges of the modern SATB choir. And the research of the Early English Organ Project, to which Johnstone's article refers, showed that the surviving physical evidence points to a standard organ pitch, in so far as there was one, that was significantly lower than previously proposed. In fact it seems to have been about A473. (The A465 pitch that we are using is a near compromise, which is much more convenient for modern reproduction organs and wind instruments, as well as for singers).

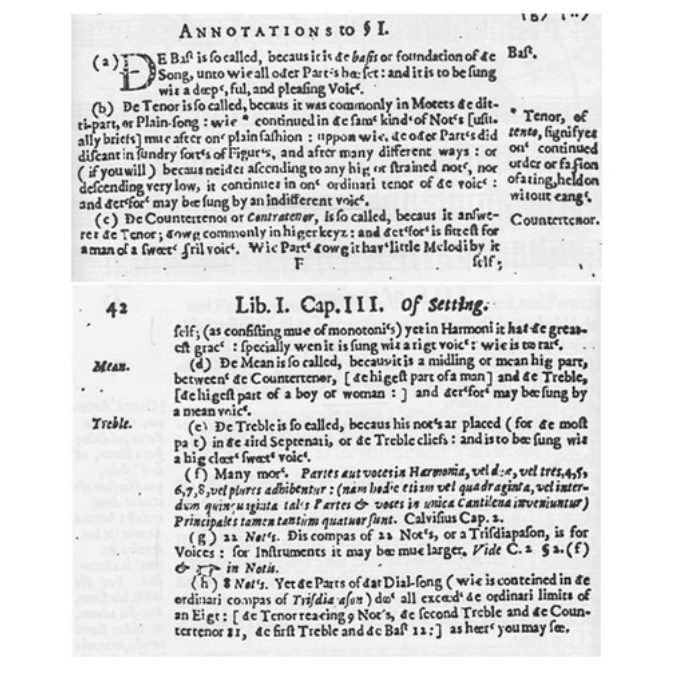

Why does any of this matter? Is it relevant to Gibbons' consort anthems anyway? Well, the fact is that when you perform the music in its original key at this theoretical 'church' pitch, so many things seem to fall into place immediately. The whole vocal sound picture is transformed in comparison to the 'minor 3rd' transposition that is normally heard in choral performance today. The bass has a proper grounding, instead of sounding baritonal. The top line sounds more gutsy and crucially has much clearer text. But, most of all, the Contratenor lines (typically the 2nd and 3rd lines in a 5-part scoring) are, or should be, sung by a particular kind of light, high tenor, giving them a brilliance and sheer intensity in the upper middle part of the consort. In standard choral performance, by contrast, these lines are typically sung by falsettist altos, required to sing in the most inconvenient part of the voice. The light, high tenor - the 'real' Contratenor voice of this period, as Andrew Parrott and others have long argued - is by far the most difficult role to fill, and that was evidently always the case, as Charles Butler wrote in 1636 (see facsimile below): "sweet and shrill", when sung with the right delicacy, but "too rare". Happily, we have some of this rare breed in our project! As for whether Gibbons expected his consort anthems to sound at this 'church' pitch and with these vocal colours, we can never know. There are issues concerning the Christ Church source for the anthems (upon which our performances are based) which continue to provoke disagreement, and some argue for a lower 'domestic' pitch. We think that there are strong reasons for choosing A465, and since (to our knowledge) the music has never been recorded this way before, it is high time for it to be heard. The implications of A465 for the consort instruments are also significant, and that will be the subject of the next post. Only a few days until our first concert, in Stour Music Festival (June 25th) and everyone is excited at the prospect of taking part in such great music. We want to get a conversation going about Gibbons’ consort anthems and about verse anthems generally, since we think it is a repertoire that has been largely neglected and misunderstood for far too long. So please join us and help to spread the word.

Find out more here: http://www.stourmusic.org.uk/concerts-2016/fretwork-and-the-magdalena-consort |

|